Mental Health Statistics in Malaysia Before and During the Pandemic

Key Insights

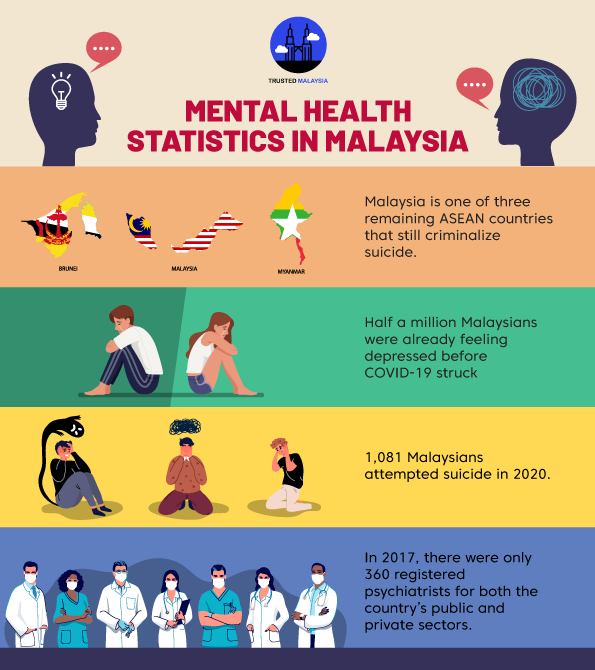

- Malaysia is one of three remaining ASEAN countries that still criminalize suicide.

- Nearly 500,000 Malaysians were already feeling symptoms of depression before the pandemic started (according to the 2019 National Health and Morbidity Survey).

- In 2017, there were only 360 registered psychiatrists for both the country’s public and private sectors.

- In 2019, the states of WP Putrajaya, Negeri Sembilan, Perlis, Sabah, and Melaka had the highest prevalence of adult depression in the country.

- The Malaysia Communications and Multimedia Commissions reported that out of 14,000 students surveyed, 70% experienced online harassment in 2019.

- A total of 1,081 suicide attempts in Malaysia were recorded in 2020 alone.

- In August 2020, a signature campaign to decriminalize suicide and spread mental health awareness and support in the country was launched.

- Only RM344.8 million was allocated for mental health care in 2020. This figure represents less than 2% of Malaysia’s total budget for healthcare for the year.

- By 2030, mental health statistics in Malaysia are expected to impact the economy by US$6 trillion.

A March 2021 ASEAN Today article sheds light on growing mental health issues in Malaysia with the presence of COVID-19 seemingly aggravating them. It mentions social isolation, economic insecurity, and the loss of loved ones as major contributors to anxiety, stress, and depression.

But even before the pandemic, the 2019 National Health and Morbidity Survey showed that nearly half a million Malaysians were already feeling symptoms of depression.

And over the course of two decades, mental health statistics have tripled and are expected to impact the economy by RM25.3 trillion come the year 2030.

The lockdowns imposed in Malaysia also contributed to what Malaysian Mental Health Association’s president Dr. Andrew Mohanraj called “a two-fold increase” on mental health issues.

A section below discusses the issue of suicide more thoroughly. However, it’s worth mentioning here that rates of suicide and attempted suicide have had a marked increase since the country’s initial lockdown period.

Depression Statistics in Malaysia Before the Pandemic

An inaccurate perception of mental health issues is arguably one of the main culprits of mental health stigma in Malaysia.

A 2019 report by the International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences showed that over 50% of Malaysians believed that it’s the sufferer’s fault for their condition and that 80% believed that mental health problems do not even exist.

But as reported by clinical psychology non-profit website, Hui Bee, every three in ten Malaysians aged 16 years old and above reported some sort of mental health issue in 2015. This made up 29.2% of respondents of the 2015 National Health and Morbidity Survey.

In Kuala Lumpur alone, the prevalence of mental health issues went up to 39.8% in 2015. More female respondents were reporting mental health concerns (30.8%) compared to male respondents (27.6%).

In 2019, the states of WP Putrajaya, Negeri Sembilan, Perlis, Sabah, and Melaka had the highest prevalence of adult depression in the country.

In the span of a decade, mental health problems increased from 10.7% in 1996 to 11.2% in 2006. And nearly a decade after (in 2015), it rose to 29.2%.

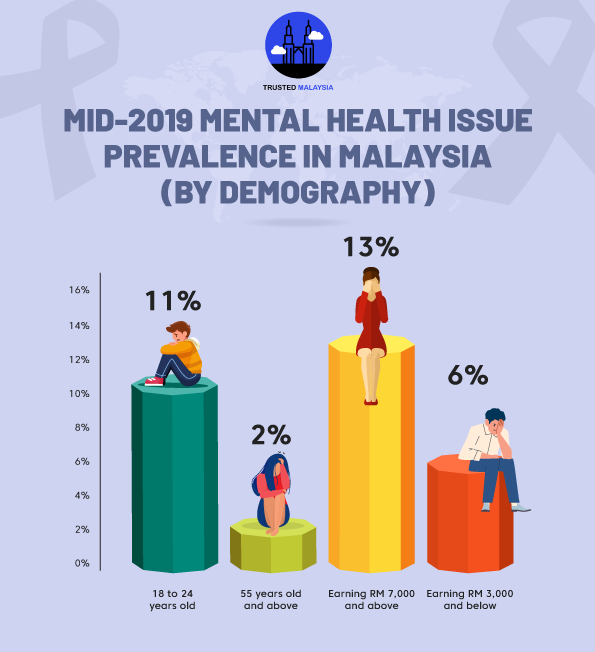

By 2019, 1,027 Malaysian respondents on a survey on the prevalence of mental health issues in the country showed a clearer demographic picture. Eleven percent of respondents aged 18 – 24 years old said they experienced mental health issues compared to only 2% of respondents aged 55 years old and above.

Income also factored in, as the graph below shows. 13% of respondents who earned RM7,000 a month and more were more likely to have experienced mental health issues compared to just 6% of those who earned RM3,000 monthly and below.

The website Trading Economics pegged the average Malaysian wage to be about RM2,933 per month in 2020. This shows a significant decrease from 2019’s average of RM3,224 per month.

A surge of mental health conditions was reported by The Befrienders, Malaysia’s most popular emotional support center. Between March 28 and December 1, 2020, 43,000 calls on its Psychological First Aid hotline.

34% of calls between March and May alone were related to COVID-anxiety with over a third being suicidal in nature.

Suicide Statistics in Malaysia

Malaysia is one of three remaining ASEAN countries that still criminalize both attempted suicide and suicides. Myanmar and Brunei also consider it a crime to take one’s own life.

In one extreme example, a 28-year old man who attempted suicide by jumping off his balcony was penalized RM3,000 or three months in jail if he fails to pay the fine. Instead of offering mental health assistance, public prosecutors wanted to give the victim a “lesson” for “inconveniencing many parties”.

In 2020 alone, a total of 1,081 suicide attempts in Malaysia have been recorded. Between March and October 2020, 266 people have committed suicide for reasons ranging from economic debt to family problems.

But by August 2020, a growing number of outraged Malaysians have started a campaign to decriminalize suicide and spread mental health awareness and support in the country. This petition was done via the Change.org platform and has since gathered 16,800 signatures (and counting).

Lee Lam Thye, a member of the Mental Health Advisory Council, argued that decriminalization could actually help lower the country’s suicide rates. He said in a statement:

“When suicide is considered a criminal act, suicide attempts are hidden and suicide deaths will go unreported, thus giving a false perception that suicidal behaviors are less prevalent.”

Malaysia’s Health Minister, Adham Baba, also encouraged the government to amend its laws and make way for a more humanized approach to mental health. He describes the efforts to provide patient physiological support as challenging but firmly believes that:

“Efforts towards decriminalizing suicide attempts will open up opportunities for patients with depression or suicidal behavior to come forward, without stigma, for treatment and recovery.”

Cyberbullying Statistics in Malaysia

With the popularity and prevalence of social media and gaming platforms comes a worrying new phenomenon: cyberbullying. This is thoroughly investigated in a March 2021 OICT-CERT paper called “Cyberbullying via Social Media: Case Studies in Malaysia.”

It states how 8 out of 10 schoolchildren in Malaysia have experienced some form of bullying in their schools, with alarming incidents of brutal physical/online bullying ending in death.

One of the more extreme cases of cyberbullying happened in 2017 with 20-year old Teh Wen Chun, an engineering student living in Penang. After leaving a suicide post on his Facebook page and jumping from his 17th floor flat, his father revealed that Teh Wen Chun was extremely stressed by cyberbullying posts that tarnished his image online.

More recently in May 2019, 16-year old Davia Emilia had an Instagram poll asking her followers if she should live or die. 69% of them voted for her to die, and on the same day, Davia jumped to her death from their 3rd floor Sarawak apartment.

A 2019 survey conducted by the Malaysia Communications and Multimedia Commissions of 14,000 students showed that a whopping 70% experienced online harassment. They described being sent “improper pictures or messages” and called “mean names” online.

The Malaysia Computer Emergency Response Team (MyCERT) underlines these statistics with reports of 260 cyber harassment cases received in 2019 alone.

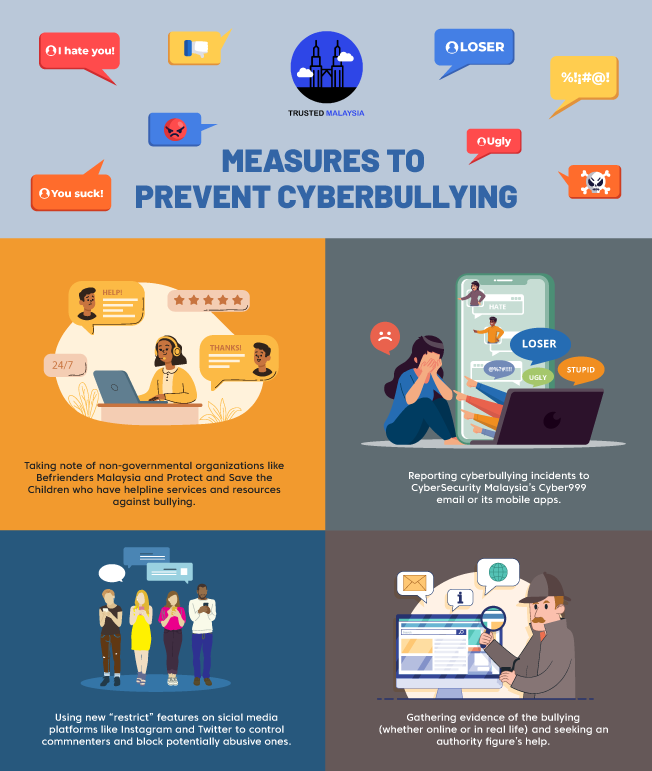

The OIC-CERT journal goes on to publish intervention measures to prevent cyberbullying from claiming more victims. Some key takeaways include:

- Taking note of non-governmental organizations like Befrienders Malaysia and Protect and Save the Children who have helpline services and resources against bullying

- Reporting cyberbullying incidents to CyberSecurity Malaysia’s Cyber999 email or its mobile apps

- Using new “restrict” features on social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter to control commenters and block potentially abusive ones

- Gathering evidence of the bullying (whether online or in real life) and seeking an authority figure’s help.

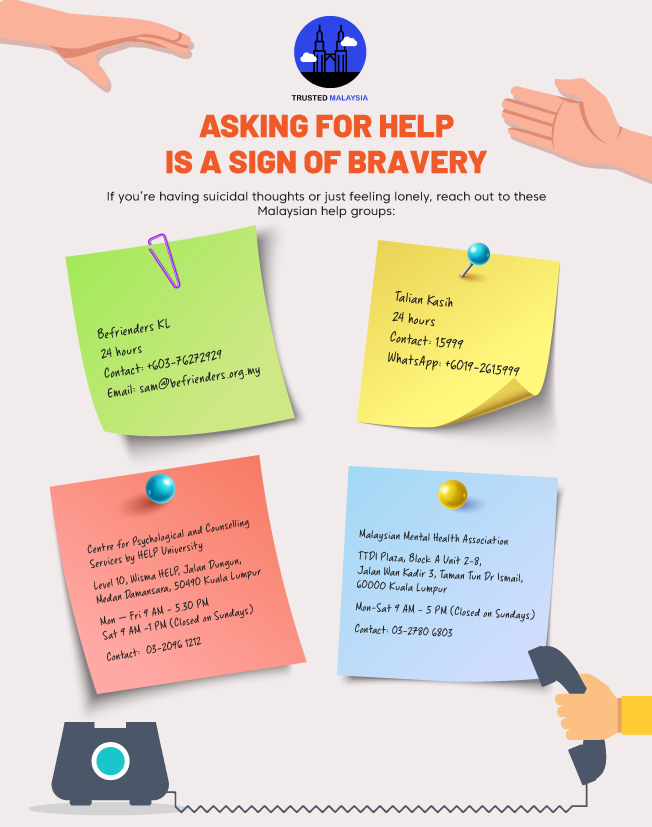

Smart Local Malaysia also published a comprehensive list of counselling and mental health services and hotlines in the country if you need professionals to listen to your concerns.

Malaysia vs. Other Southeast Asian Countries’ Mental Health Statistics

A 2018 national survey in Singapore revealed that 1 in 7 people have gone through a mental health condition in their lifetime. In Malaysia, 1 in 3 adults (aged 16 years and above) surveyed in 2020 have reported a mental health condition.

The top three mental conditions reported in Singapore include major depressive disorder, alcohol abuse, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In Malaysia, one in five youths aged 13 to 17 years old have had depression, two in five have anxiety, and one in 10 has experienced stress.

Singapore only has 2.8 psychiatrists per 100,000 residents, while Malaysia only has 1.27 psychiatrists per 100,00 residents.

Meanwhile, the Philippines only has a ratio of 0.52 psychiatrists per 100,000 persons. But Indonesia’s 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 residents are the lowest among these South East Asian countries by far.

Malaysia has a reported 10.1% of its youth attempting suicide in 2020. In the Philippines, an even more alarming 16.8% of youth aged 13 to 17 years old have attempted to take their lives.

In Indonesia, a whopping 45% of its youth have done self-harm and 19% reporting to have had suicidal thoughts.

The trend of the scarcity of mental health professionals among these Southeast Asian nations and the corresponding statistics on suicide and mental health is definitely worth investigating.

Mental Health Statistics in Malaysia During the Pandemic

When the country had its initial lockdown period between March 18 to June 9, 2020, there were 78 cases of attempted suicide in Malaysia. This was a significant increase from the 64 suicide cases of the previous, non-COVID year.

Isolation, economic hardship, uncertainty, fear, anxiety, and helplessness can all take a toll on one’s mental health. It’s why the country’s Ministry of Health released mental health and psychosocial support documents to help its citizens understand and cope with mental health concerns during the pandemic.

It outlined common responses to COVID-19 which include stress, worry, anxiety, and other individual responses to the crisis situation. Some of the responses mentioned in the document include:

- Worry over family members being infected

- Fear of dying and losing loved ones

- Feeling helpless and unable to protect loved ones

- Stress and separation anxiety especially due to separation due to quarantine

- Fear of being placed under COVID home surveillance

- Avoiding health facilities due to fear of infection

- Fear of not being able to work during isolation, or of being dismissed from work

- Feelings of helplessness, boredom, loneliness and depression due to being isolated

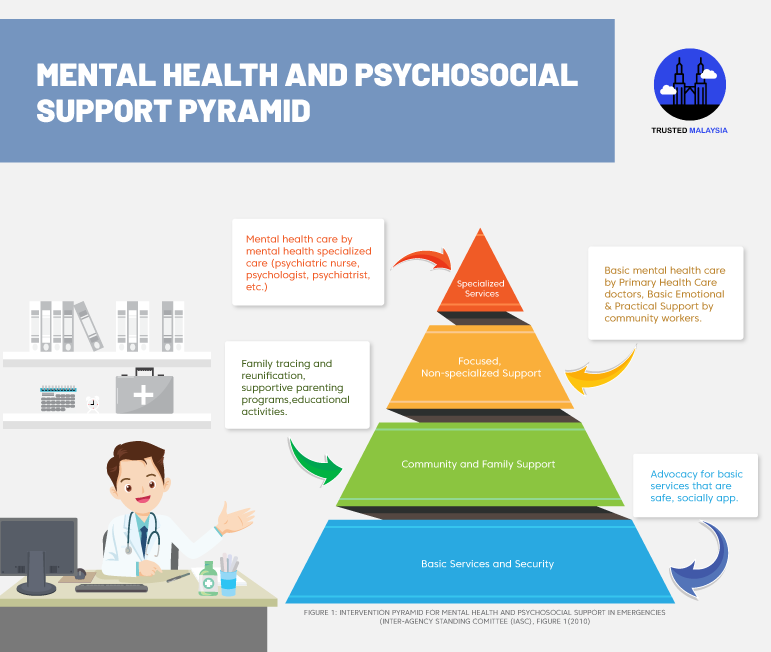

The MOH formed a Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) service delivery to COVID-19 victims that follow the principle of basic needs provision. This was then followed by the restoration of community and family support, then by focused and specialized services to a smaller subgroup within those affected by the crisis.

This MHPSS model illustrates its role in each level of need.

How Is the Malaysian Government Handling Mental Health Issues?

In a New Straits Times article published in January 2017, Malaysian Mental Health Advisory Council member Tan Sri Lee Lam Thye revealed that there were only 360 registered psychiatrists for both the country’s public and private sectors.

He expressed the need to address both the shortage of competent experts along with alarming mental health figures on the rise. One of his recommendations to the Malaysian government is to urge more doctors to specialize in the psychiatric field.

At the time of the article’s publication, Tan Sri Leem Tam Thye predicted mental illness would be “the second-biggest health problem affecting Malaysians after heart diseases by 2020”. He suggested a community-based approach with the government putting in greater effort to destigmatize mental illness.

But then the pandemic happened.

With the country’s unemployment rate rising to 5.3% in May 2020 from 5% in April, around 10.22 million people have received COVID-related aid. The aid has totalled RM10.9 billion by June 26, 2020.

The country’s national budget for 2020 reflects unpreparedness as only RM344.8 million was allocated for mental health care. This figure represents less than 2% of Malaysia’s total budget for healthcare.

Even with the offer of stimulus assistance, the government has yet to do something concrete to address and treat the psychological and emotional tolls on Malaysians during the pandemic.

And with the clamor for decriminalizing suicide in the country growing, perhaps the Malaysian government can begin to acknowledge that punishment for people already in mental and physical distress is not the way to go, especially during a pandemic.

Only then can solid plans to support mental health initiatives to improve the country’s overall mental health and wellbeing can come to fruition.

One of these plans is for the Malaysian Mental Health Association (MMHA) to promote first aid responders for mental health. It’s aimed to help identify signs of behavioural distress or crisis and provide assistance for mental health crises.